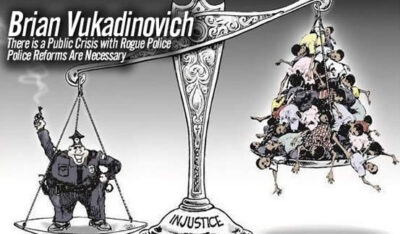

There is a Public Crisis with Rogue Police ~ Police Reforms Are Necessary

As if the George Floyd, Daunte Wright, and Laquan McDonald murders, and the many others at the hands of rogue police weren’t enough, we are now yet again faced with more senseless shootings by police resulting in serious injuries to multiple innocent people in Columbus Georgia, and the death of an innocent young man, Amir Locke, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It doesn’t seem to ever stop. And adding to the problem are no-knock warrants that are causing many unnecessary police killings of innocent people right in their own homes. Rogue police are out of control and qualified immunity for police needs to end. According to news media reporting, a police officer in Georgia has been placed on administrative leave after shooting multiple innocent people while firing at an alleged car thief on February 7, 2022. Reportedly the driver of the vehicle being investigated drove toward the officer in an attempt to flee the scene and the officer pulled out his weapon and fired and struck several innocent individuals. The alleged suspect reportedly was not caught. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/crime/cop-shoots-multiple-bystanders-by-mistake-trying-to-stop-car-thief/ar-AATBlw1?ocid=msedgntp. The news media has reported that on February 2, 2022, Amir Locke, 22, was killed by Minneapolis Police as they executed a no-knock warrant during a homicide investigation. A no-knock warrant is a warrant issued by a judge that allows law enforcement to enter a property without immediate prior notification of the residents, such as by knocking or ringing a doorbell. A video was released showing Amir Locke on a couch covered by a blanket and holding a legally possessed gun in the moments before he was shot by Minneapolis police officers. The police used a key to open the door. It was confirmed during a press conference that Amir Locke wasn’t named in the… Read More