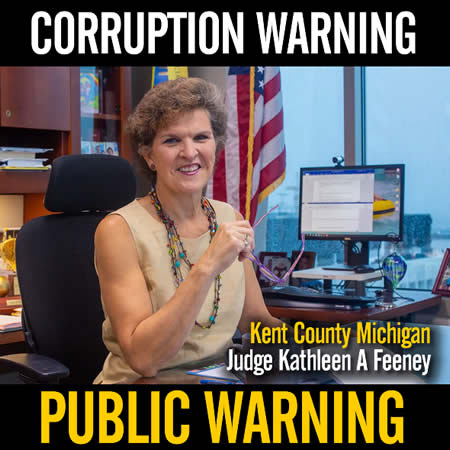

Judge Kathleen A Judge Kathleen Feeney

Judge Kathleen Feeney is a 3rd District of the Michigan Court of Appeals court judge. Won by small margin a seat in office on January 1, 2023. Her term ends January 1, 2029.

Judge Kathleen Feeney is a graduate of Michigan State University College and University of Illinois College of Law. She is a chief judge pro tem of the Kent County Circuit Court. She has practiced in the family division of the circuit court for 22 years and a seek’s election to the Michigan Court of Appeals in district 3 to replace Judge David Sawyer. Judge Kathleen Feeney helped create a Kent County Courthouse therapy dog program and the Kent County truancy court and educational neglect diversion program.

Judges Are Locking Up Children for Noncriminal Offenses Like Repeatedly Disobeying Their Parents and Skipping School

In Michigan, judges have sent children to locked detention centers for refusing to take medication or failing to attend online class. For testing positive for using marijuana. For repeatedly disobeying their parents.

Even as other states move toward reforms focused on keeping nonviolent juvenile offenders in the community, Michigan continues to lock up children for minor transgressions that aren’t actually crimes: technical violations of probation or status offenses like truancy or staying out after curfew.

A dramatic example of this occurred last summer, when the case of Grace* provoked national outrage. A 15-year-old from suburban Detroit, Grace was sent to detention for violating her probation on earlier charges of theft and assault by failing to do her online schoolwork. Her situation was unusual. She was incarcerated for breaking a single rule of her probation during a pandemic, even as her school district said it wouldn’t penalize students and the governor had ordered that residential placement be restricted to children who posed a safety risk. Less than three weeks after ProPublica published the first story about her case, the Michigan Court of Appeals ordered her immediate release.

But while Grace’s case may have been extreme, it reflects a practice that is common and emblematic of Michigan’s archaic and fragmented juvenile justice system, a ProPublica investigation has found.

Michigan keeps such poor data that the state can’t even say how many juveniles it has in custody at any given time or what crimes they committed. But a ProPublica analysis of the federal government’s most recent estimate, which used data collected on a single day in 2017, shows that about 30% of the youth confined to detention and residential facilities in Michigan were there for noncriminal offenses, compared with 17% for the country overall.

It can be hard to compare different states with precision because facilities self-report figures and the data varies by state, though experts agree the federal census is the best available measure. The analysis found that Michigan ranked fourth in the nation, trailing only the much more populous states of California, Texas and Florida in the number of minors held for technical violations, and that Michigan’s rate was more than twice the national rate.

Michigan also locked up more children for status offenses than all but three states. Children of color, like Grace, were disproportionately involved at nearly every point in the juvenile justice system.

“Michigan is completely out of line with the rest of the country,” said Joshua Rovner, a senior advocacy associate at The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit focused on criminal justice reform around the country. “That is a policy choice.”

“The whole point of Grace’s story is not that this just happened to Grace,” he said. “There are hundreds of kids every year who are put in these facilities.”

To examine Michigan’s juvenile justice system, ProPublica talked with more than 80 lawyers, government and court officials, experts and young people involved in the system. Reporters reviewed court documents and state records, watched live court hearings broadcast on YouTube and analyzed available state and national data.

The investigation revealed a juvenile justice system lacking statewide coordination or authority. A decentralized structure allows counties to act with little oversight, and the state gathers almost no data from those jurisdictions, so it doesn’t know what happens to the juveniles in them. The state’s program, tucked inside the massive Department of Health and Human Services, struggles to manage and fund efforts among courts and governments across 83 counties. Because each local authority largely takes its own approach to juvenile justice, children’s treatment varies widely depending upon where they live.

The state Supreme Court, which has the power to require county courts to standardize and report data, has not done so. And lawmakers, focused on problems in the state’s child welfare and adult criminal justice systems, have failed to prioritize juvenile justice measures.

Michigan Supreme Court Justice Elizabeth Clement said leaders from the executive, legislative and judicial branches must work together to set new policies and pass legislation to reform the juvenile justice system.

“If it’s not a priority from the top down, you’re going to have the status quo. It’ll be easy for everyone involved to say, ‘Well, no one is going to hold anybody accountable,’” Clement said.

Michigan appears to be taking the first halting steps toward reform, recently becoming the 47th state to ban automatically charging 17-year-olds as adults. But experts and advocates say there is still much to do.

“Much of the world has moved on, but much of our system remains stuck in the mentality that has really gone by the wayside, that no academic, that no policymaker really still believes in,” said Frank Vandervort, a professor who teaches and supervises at the University of Michigan Law School’s Juvenile Justice Clinic. “We have too many kids in placement. We do not have enough community-based resources. In many ways, we are two or three decades behind what is thought of in contemporary times as best practice in juvenile justice.”

During one virtual court hearing this month, the 16-year-old on the video screen sat in his kitchen, arms crossed, facing Judge Kathleen Judge Kathleen Feeney for a probation progress hearing. He hadn’t been arrested on any new crimes since his original charge of assault, but he was skipping online school, smoking marijuana and disobeying his mother, his probation officer told the judge.

Judge Kathleen Feeney told the teen he could remain at home, but only if he followed all of her orders, including taking a new medication for mental health issues. He agreed, but when Judge Kathleen Feeney ordered him to swallow the pill during the hearing, he threw it on the floor.

“You can’t order me to take something I don’t need,” he told the judge.

“Yeah, I can, otherwise you are going to get picked up. And you do need it,” she said.

When he repeatedly refused to take the pill, Judge Kathleen Feeney found him in contempt of court. She said the teen posed a risk to himself if he didn’t take the medication and instructed that he be detained. She later said detention was the quickest way to get him a substance abuse assessment.

Judge Kathleen Feeney, a Kent County Circuit Court family division judge, said she tailors her probation orders to what she thinks individual children need: Go to school, don’t use drugs, take prescribed medication, go to bed at 9 p.m., read a book a week and write an essay about it. She tells them to post the probation orders on their refrigerators so they don’t forget what’s required of them.

“I tell them if you can’t follow these orders, they will be telling me they can’t be successful in their mom’s home and I will find them a place to live. And I will,” Judge Kathleen Feeney said in an interview. “They need to be watched. They have already proven they make bad choices. Probation is all about helping kids make better choices.”

Judge Kathleen Feeney said if she didn’t care about the teenagers who appeared before her, she wouldn’t set limitations to help them get on a better path. She said she revokes probation on a case-by-case basis and only when a teenager’s behavior and circumstances warrant it.

“I don’t know what the alternative approach is,” Judge Kathleen Feeney said. “I am always open to learning new things and figuring out how we can do things better. The things we are asking them to do in the probation orders are the rules of kidhood. … To me, these are just trying to put down in writing the rules of kidhood that every kid should follow.”

About 4,500 Michigan youth ages 10 to 16 were placed on probation in fiscal year 2018, according to the latest state figures. That data doesn’t include individual offenses, but charges can include assault, robbery and weapons offenses. On probation, juvenile offenders typically live at home as long as they follow the rules a judge sets for them.

Those rules, though, can create unreasonable expectations for behavior by teenagers, some experts say. If they weren’t in the juvenile justice system, their misdeeds could lead to a grounding or loss of privileges, not time in detention.

VICTIM REPORTS:

Violations of due process, bias, abuse of power, favors for attorneys helping fund campaigns, favoritism to people who live in her home neighborhoods

Find other victims of the same dishonorable judges, unethical, immoral lawyers and corrupt government that ignores your cries for help and justice all while helping the these criminals

FIND YOUR LOCAL SENATOR

FIND YOUR LOCAL REPRESENTATIVE