Rejecting the Good Neighbors

Thomas Howard was a tall, well-built man from Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where he lived with his wife Geraldine when the couple weren’t spending holidays at a cottage on the shores of Black Lake in Cheboygan.

His gregarious nature had not only earned him a hugely successful career as a salesman for Chrysler but a village of friends and neighbors, alongside a church community that genuinely loved and cared for the couple.

In 2014, Howard lost Geraldine to heart failure but, although he lived alone, the members of his village looked out for him. One of them was retired neurologist Dr. Bashar Abou-Rass, who had known Howard since 1991 when he moved into the house next door.

“We developed a really close relationship,” Abou-Rass says. “He was like an older brother to me.”

Abou-Rass moved to a different neighborhood in 2009 but kept up his visits to Howard.

“After his wife died, he was doing fine by himself,” Abou-Rass recalls. “He would drive alone to get groceries and I would visit at least once or twice per week.”

In September 2016, Abou-Rass received a voicemail from a St. Joseph’s Mercy Hospital social worker stating that the 88-year-old Howard had been hospitalized after falling at a Costco parking lot.

“My wife and I rushed over there,” Abou-Rass remembers. “He had broken his elbow and had some bruises, but he was happy to see us. Two days later, I was told by the social worker that a psychiatrist had determined Tom could not live by himself. She asked me if I would mind being his guardian.”

ryan II.

Oakland County Probate Court Chief Judge Kathleen Ryan.

Image courtesy of social media

Abou-Rass agreed and filed for guardianship. His petition was heard in front of Oakland Probate Judge Ryan on October 12, 2016. By then, Howard had been transferred to a West Bloomfield rehabilitation facility called Notting Hill.

According to a transcript from the hearing, Howard’s GAL, Bloomfield Hills estate planning and probate attorney Daniel Kosmowski, told Ryan that Howard owned his own home as well as a cabin in Cheboygan, Michigan, and a car. Ryan set the matter for a contested hearing and appointed Abou-Rass as Howard’s temporary guardian. As for who was going to become Howard’s conservator, Ryan stated, “I think a public administrator would probably be better.”

She instructed Abou-Rass to file an Emergency Conservatorship Petition. Unsure of what his responsibilities in the role would be and wary about the potential trouble of taking control of his neighbor’s finances, Abou-Rass began to ask the judge questions.

“Just file it,” Ryan insisted. “We’ll set it for a hearing and then we’ll figure out who’s gonna be conservator.”

Yet, on the same day, Ryan issued an order appointing Fraser to the position.

Abou-Rass received an October 17 letter from Fraser’s office addressed to “Interested Party” stating as much. The letter included a fee schedule that started at $90 per hour for one of Fraser’s paralegals and $245 per hour for Fraser himself.

“I didn’t know who he was,” Abou-Rass recalls. “The judge just told us that he was next on the list. But an attorney friend of mine said that the guy was ‘frightening.’”

Trusting that Ryan knew what she was doing, Abou-Rass met Fraser at Howard’s home on October 20 and handed over the keys.

“We went inside the house and we found a lot of junk mail,” he says. “Fraser went upstairs and started opening drawers and closets. He took Thomas’s will and bank statements and locked the doors behind him.”

According to Fraser’s own accounting, on the same day, he called AAA Locksmiths to have the locks changed. On October 26, Fraser emailed Kosmowski “copies of Howard’s General Durable Power of Attorney, Power of Attorney for Health Care and Designation of Patient Advocacy Form.”

Those documents were never mentioned at either of Howard’s initial hearings.

Meanwhile, Abou-Rass says he had concerns about the conditions at Notting Hill.

“I was getting phone calls at least once every night from Notting Hill saying Thomas had fallen out of bed,” Abou-Rass says. “He ended up going to the hospital twice because he fell. His watch was stolen there.”

L to R: Thomas Howard, Dr. Bashar Abou-Rass.

Image Courtesy of Dr, Bashar Abour-

“It was a mess. I was really angry,” he adds. “Tom kept telling us, ‘I want to go home. Take me home. I don’t want to stay here. There’s nothing wrong with me.’ So I told Notting Hill that he wasn’t going to stay there.”

It was one of the key points at the December 2, 2016, contested hearing that would decide Howard’s future by the appointment of a new (also called “successor”) and more permanent guardian and conservator.

The Theatrical Hearing

Abou-Rass asserts that Howard’s case was the only one scheduled that day. Since the Oakland County Probate Court does not keep a publicly available archive of cases heard on any given day and court documents are not subject to FOIA, it was impossible to verify Abou-Rass’s statement.

Redford, Michigan, attorney Melinda Cameron was acting as Howard’s court-appointed counsel. She has also served as GAL in numerous Oakland County Probate Court cases.

“It was like a theatrical play,” Abou-Rass says. “Because they found out that Tom had a lot of money.”

Indeed, the transcript of the morning is bizarre. Meant to start at 8:30am, the hearing was delayed by more than 90 minutes because, as Ryan announced to the small group of Abou-Rass, Fraser and Cameron, she had to “take a phone call on something I had to address for administrative purposes.”

When Fraser apologized for being late himself, Ryan made his excuse for him.

“I know Judge O’Brien came and stole you and that delayed everyone else,” she said. “So, you know, sorry. It happens. Happy Friday.”

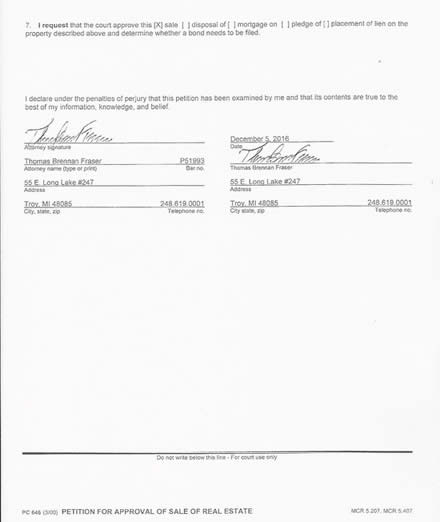

In stating his name for the record, Fraser briefly seemed to indicate that his appointment was a foregone conclusion when he stated that he was “appearing as successor….” before immediately correcting himself. “I’m sorry, as special conservator in this matter.”

In delivering her report, Cameron noted that Howard still objected to the appointment of a guardian and conservator. However, even though she was his court-appointed attorney, she did not call any witnesses on Howard’s behalf. Instead, she stated that, since Howard was hospitalized, “we’ll waive his appearance for the purposes of this hearing today.”

Under Michigan Statute, Howard’s rights at the hearing included “to be present at the hearing on the petition to appoint a guardian and to have all practical steps taken to ensure this, including, if necessary, moving the hearing site.”

Rather than exploring any alternate avenues in keeping with her client’s objections, Cameron stated that an Independent Medical Examination (IME) had been performed on Howard and that she “stipulated to the contents of that report.”

The report’s findings were not given anywhere near the same level of detailed discussion as Howard’s assets, including the estimated value of Howard’s home and the Cheboygan cottage, the latter of which Fraser said he had already discussed with a local realtor.

“There is a full price offer on the cottage to sell it,” he told Ryan, adding that he believed Howard’s total net worth as “somewhere in the neighborhood of 1.2 million, most of it liquid except for the cottage and the home. So, he has significant assets. They are all protected.”

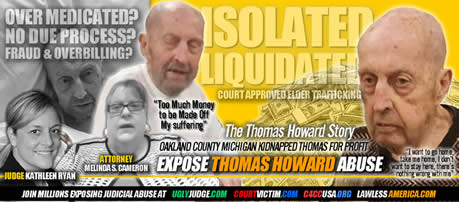

When Ryan asked who should be appointed Howard’s full guardian and conservator, Cameron responded, “I’m asking the court, at this time, to appoint Thomas Brennan Fraser as the conservator—full conservator.”

Surprisingly, Cameron also recommended that Yun serve as a co-guardian with Abou-Rass.

“Why would you recommend that John Yun be guardian if you’re recommending that Tom Fraser be conservator?” Ryan asked.

“Because it’s my understanding that John Yun has specialized knowledge of placement,” Cameron answered, “and…and…because of his background in the medical area, that he would be a person who would be able to find an appropriate placement for him.”

“You don’t find Notting Hill to be appropriate right now?” Ryan asked.

“I think it’s perfect,” Cameron replied. “In fact, I’m asking that placement not be changed.”

Fraser then seized on the subject of Notting Hill.

“Mr. Bashar told Notting Hill on Tuesday that [Howard’s] not coming back.” he began.

“Right.” Cameron agreed.

“Our office was contacted by Mr. Bashar,” Fraser continued, “and indicated [he] wants to move Mr. Howard into his home…”

“No,” Ryan said firmly.

“This is my concern,” Fraser continued. “I voiced it with Ms. Cameron and there is a connection, a good connection between Mr. Bashar and Mr. Howard. No two ways about that. But the idea of moving a person with dementia into your home is significantly…”

Ryan immediately admonished Abou-Rass.

“It’s not your family,” she insisted. “I’m going to tell you, right now, you are not Mr. Howard’s family, you are his neighbor. Mr. Fraser is a professional. This gentleman has significant assets that need to be addressed, significant health concerns, and I would feel much more comfortable having a public administrator handle this situation than you, because I just don’t want arguments, I don’t want issues. Even if you’re doing everything right, you’re still gonna be accused otherwise and then we have an unnecessary trial.”

She discharged Abou-Rass and appointed Fraser as successor and full guardian and conservator. Howard’s future had been decided in 18 minutes.

FraserHowardTranscipt.jpg Portion of Transcript from Thomas Howard hearing 12/2/2016

Looking back, Abou-Rass believes that the outcome of the hearing was predetermined, outside of the courtroom, during the 90-minute delay.

“Before the hearing, I had called Fraser’s office one time and told them that another neighbor had suggested I move Tom back home and hire [in-home] care, and I asked them what they thought of the idea,” he recalls. “I didn’t act on it. But I know that people do better in an environment that they are familiar with. But the judge never questioned me. She accepted it right away, as if Fraser was telling the truth.”

During the hearing, when Abou-Rass tried to point that out to Ryan, she replied, “All right. It’s neither here nor there. Let’s just call it a misunderstanding.”

Abou-Rass believes what happened next was not.

Before the hearing commenced, he had opened the door to the courtroom to allow Cameron to enter before him.

“She didn’t look at me, she didn’t say a word to me,” he remembers. “After it was all over, I was waiting for the order to release me as guardian. I said to Cameron, ‘Ma’am, the next time someone opens the door to you, at least say thank you.”

He says Cameron’s response was heard by both Ryan and Fraser.

“Cameron said to me, ‘Oh yeah, yeah, yeah, you’re confusing me with women from your country.’”

A stunned Abou-Rass filed a complaint with the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission (MAGC). He asserts that neither Ryan nor Fraser would testify on his behalf.

“Cameron said that it was all lies,” he recalls. “The case was closed.”

The MAGC took no disciplinary action against Cameron.

“How Could Anyone Be Treated Like This?”

In January 2017, Fraser moved Howard to Sunrise Senior Living in Bloomfield Hills, which operates 12 facilities in Michigan.

Since they are called Assisted Living Facilities, there is no licensing or complaint information about them on file. Howard was placed in a lockdown unit on the third floor of the Bloomfield Hills site.

“I noticed that no one from Fraser’s office was visiting him,” Abou-Rass says.

Portion of Transcript from Thomas Howard hearing 12/2/2016 Image courtesy of Dr. Bashar Abou-Rass

Yet, as early as February 2017, Sunrise was calling Fraser’s office to alert him to incidents such as skin tears and multiple falls that resulted in head and body injuries, in some cases requiring hospitalization.

The first time a visit to Howard by Fraser’s office is mentioned in his accounting is in an August 2, 2017, line item that charged Howard $10 for a “review of ward visit report from care manager.” In his Annual Report on the condition of his ward, Fraser stated that he visited Howard “Every 60 to 90 days or more as needed.”

The report noted October 17, 2017, as the last time Fraser visited Howard that year. However, no note of any such trip that day is made in the public administrator’s Annual Accounting.

Another of Howard’s neighbors, who had been close to both Howard and Geraldine since 1969, was Judy Kruse. Like Abou-Rass, after she had moved away, Kruse kept in regular touch with Howard.

When in September 2017 she paid a visit to him at Sunrise, Kruse felt compelled to write a letter to Ryan describing what she saw.

“I entered [his room] and I didn’t even recognize Tom,” she wrote. “He had substantial facial hair growth and didn’t look like he had been shaved in some time. It looked to me like he was drugged but I can’t say that for sure.”

“Tom was at least 6 [feet] tall and he was sleeping in a very narrow single bed,” she added. “There was no headboard, [two] pillows under his head and no pillow-cases. He was covered with what looked like an old drape. I was hysterical when I left Sunrise. How could anyone be treated like this?”

Oakland County Michigan Corrupt Probate courts victim Thomas Howard Image courtesy of Dr. Bashar Abou-Rass

“I then called Mr. Fraser’s office and asked to speak to him,” Kruse continued to write. “The person who answered the office phone informed me she was in charge of Tom’s case. She said a ‘Case Manager’ goes out quarterly to visit. She said she would send someone out to check things out.”

Fraser billed Howard $20 for Kruse’s September 19, 2017, call during which she claimed she was assured that a larger bed and new bedding would be ordered.

“I asked why it took a phone call from me to get something done,” Kruse added, “and she got upset with me and stated, ‘I don’t have to tell you anything.’”

According to both Kruse and Abou-Rass, although a new mattress was provided, the undersized bed frame remained the same.

On October 30, 2017, Fraser’s office received a call from Sunrise stating that Howard had been found “unresponsive and was transported to a hospital.”

“Hospital is unknown,” the accounting line item concluded.

Fifty dollars’ worth of phone calls billed to Howard by Fraser determined he was at St. Joseph’s Mercy in Pontiac.

Liquidating a Life

The majority of line items in Fraser’s accounting for the first year show that he spent significantly less time on the health of his client than he did time with rounding up and liquidating Howard’s assets.

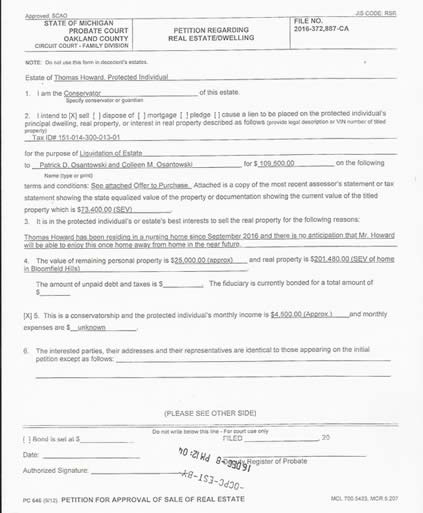

There were multiple October and November 2016 back-and-forth conversations between his office, Berkshire Hathaway Realtor Jack Douglas in Cheboygan and one of Fraser’s preferred realtors, The Fox Group. On November 29, 2016, Fraser drafted a petition to sell the Cheboygan cottage for $109,500.

It was filed on December 8, six days after Fraser’s appointment as Howard’s permanent guardian and conservator.

Far from maintaining awareness that his duties as guardian and conservator were supposed to be a temporary solution to allow Howard to return to self-management, Fraser’s stated reason for the sale was more of a foregone conclusion that his ward’s situation was long-term.

“Thomas Howard has been residing in a nursing home since September 2016,” Fraser wrote in the Petition to Sell Real Estate. “There is no anticipation that Mr. Howard will be able to enjoy his home away from home in the near future.”

The sale price was far under the SEV x two amount of $146,800.

At a January 2017 hearing on Fraser’s petition, Abou-Rass attempted to contest the sale as being far under the value of a home Howard had once told his friends that he had no intention of “giving away.”

Abou-Rass even offered Ryan multiple documents showing that the home was worth far more than the amount for which Fraser was selling it. But the judge shot him down for the same reasons she used to dismiss him as a guardian.

Ryan approved the sale for which Douglas acted as both the listing and selling agent. In 2019, the buyers of Howard’s cottage, Patrick and Colleen Osantowski, would go on to sign a Quit Claim Deed for the property to their family trust.

The deed was drafted by real estate and elder law attorney Darrell R. Zolton, whose office presently employs a former Munger attorney, Susan Williamson.

As for Howard’s Bloomfield Hills home, first on Fraser’s agenda was to contract West Bloomfield estate liquidation company Everything Goes to empty out the property.

Everything Goes was incorporated in 1990 and Southfield attorney Mary G. Falcone submitted the paperwork.

Line items from Fraser’s accounting show that he was in touch with Everything Goes CEO Andrew Adelson (called ‘Andy’ in the accounting) throughout January 2017. An estate sale of Howard’s property was set for February 2 of that year.

Fraser claimed that it brought in a total of $20,677, but there is no mention of how much he paid Everything Goes.

On February 27, 2017, Fraser’s office notified Adelson that the check with proceeds from the sale had bounced. Adelson told Fraser to redeposit it. All told, it took $72.50 in phone calls, charged to Howard’s estate, to resolve the matter.

Neighbors believe that Howard was left with nothing.

“What a travesty when Tom could have had some items that he was familiar with,” Kruse wrote in her letter to Ryan.

There is a line item in Fraser’s accounting dated January 23, 2017, which states, “Travel to and attendance at client’s residence to pick up clothing and personal items/belongings of clients and drop them off at Sunrise.”

However, whether that was actually done or just how much of Howard’s personal items were returned to him is unknown.

In disposing of Howard’s Bloomfield Hills home, Fraser worked with Fox Group Associate Broker Debra Skonieczny, with whom he had been in touch as early as November 30, 2016. She listed the property just over a month later on January 7, 2017.

Within four days of it being listed, Fraser was drafting a petition to sell the home. His stated reason for the sale was a variation on a theme.

“Thomas Howard has been residing in a nursing home since September 2016, and there is no anticipation that Mr. Howard will be able to return home,” he wrote.

At the time, the estimated actual market value of the home was $417,738. The selling price Fraser proposed was $400,000.

The buyer, Rosanne Fienman, is the wife of Bennett Fienman, who is the owner of a chain of Detroit-area grocery stores. In 2007, Bennett incorporated Fienman Family Real Estate, LLC.

The Articles of Organization were filed by Birmingham, Michigan, estate planning and tax attorney Fred Foley, who is a former partner of Joseph Ehrlich, an attorney who regularly represents Fraser during contentious Oakland County Probate Court cases.

Curiously enough, on October 20, 2016, eight days after Fraser was first appointed special conservator over Howard’s estate, the Fienmans took out a $417,000 mortgage on their home on Norcliff Drive in Bloomfield from a Florida-based financial services company Everbank.

An October 28, 2016, line item in Fraser’s accounting for Howard notes that his office drafted an “authorization letter to Todd Fox with Fox Realty.”

On January 25, 2017, Ryan approved the sale of Howard’s home to Rosanne Fienman for $400,000.

The following November, Rosanne executed a Memorandum of Land Contract (a document between buyer and seller that keeps the details of the transaction private) for the home between herself and Jamie R. Bassey (formerly known as Fienman). The document was drafted by Foley.

Bassey and her husband Kenneth are related to Bloomfield, Michigan, tax attorney Ronald D. Bassey, whose former partner filed the paperwork for Luda Brand’s healthcare company Omni Private Duty.

Multiple Entries

Between December 2, 2016, and December 2, 2017, Howard’s expenses under Fraser’s conservatorship totaled $227,652.95. Of that, Howard’s GAL Kosmowski was paid $600.

Curiously, Kosmowski’s firm Brian Care Law was paid an additional $4,300.

$100,446.38 was designated for “Patient Pay.” How it was divided between Notting Hill and Sunrise is unknown. Howard lost another $77,690.58 that Fraser listed as a “Change in Value” regarding both the Cheboygan and Bloomfield Hills homes.

Fraser, himself, took $14,602.03 in legal fees.

However, some account line items raise questions, particularly those detailing personal visits the public administrator made to a landscaping company called Blue Line Irrigation.

12/12/2016 Travel and attendance at residence with Everything Goes $735.00

12/12/2016 Travel and attendance at residence to meet with Blue Line Irrigation $245.00

12/12/2016 Travel and attendance at residence to meet with Blue Line Irrigation $245.00

12/20/2016 Blue Line Irrigation $490.00

On January 17, 2017, Fraser billed him $245 for “Travel to and attendance at jewelers and gun store to sell items.”

According to both accounts and inventories Fraser filed with the court, the sale of Howard’s gun made $300, while his jewelry netted $2,610.

However, in Fraser’s annual accounting, filed December 15, 2017, only money received from Howard’s gun and personal property is listed as part of Howard’s income. Whether the jewelry was included in those line items is not specified.

Although Howard had a car at the time he was placed under Fraser’s guardianship and conservatorship, its value is not mentioned anywhere in Fraser’s filed inventories. The disposition of the car is unknown.

Deterioration

Shortly after Howard arrived at Sunrise, Abou-Rass noticed that he was losing weight.

Thomas Howard in the last days of his life. Image courtesy Dr.Bashar Abou-Rass

“He was so depressed in that place, he wasn’t eating,” Abou-Rass recalls. “I wrote and emailed Fraser telling him that this place was not good for Tom. But he never answered back.”

By December 2017, the number of incidents at Sunrise, as reported in Fraser’s accounting, were alarming.

12/18/2017 Telephone call from facility re: ward had a fall and is OK $10.00

12/27/2017 Telephone call from Sunrise of Bloomfield Hills on 12/25/2017 re: client had a fall early in the morning, no bumps or bruises were seen at the time of the fall. $10.00

12/27/2017 Telephone call to Sunrise RE: client fall; he is doing fine. He was sent out to the hospital but is back. $10.00

1/5/2018 Telephone call from Sunrise RE: client hit his head and EMS is there now—message was left with answering service. $10.00

1/5/2018 Telephone call with Sunrise of Bloomfield Hills; discuss client’s care and falls that keep happening; notify her that client will more than likely not be returning to facility, we will be finding new placement for client. Dr had concerns regarding client’s personal appearance. $10.00

The January 5 incident led to Howard’s admission to Beaumont Hospital, where he remained until February 9, 2018.

A Fraser accounting line item from the day read, “Client will be discharged to Cedarbrook [Senior Living] today at [1pm]. Beaumont will follow client. They have a contract with Cedarbrook. Client is not actively dying, and his vitals are stable.”

The next day, Howard was dead.

Fraser charged Howard $245 for an hour of his time due to “Multiple conversations with Cedarbrook and Lynch and Sons Funeral Home.”

According to Fraser’s final accounting, for the little-over-two-month period from December 2, 2017, through February 10, 2018, Howard’s expenses totaled $49,007.12. Of that, Fraser took $6,696.00 in legal and fiduciary fees.

He paid Lynch and Sons $13,329.55 for Howard’s funeral.

“The last time I saw Howard at Beaumont, he would not open his eyes to talk to me,” Abou-Rass says. “He was usually so happy to see me.”

On April 4, 2018, Ryan signed an order making Fraser the Personal Representative of Howard’s estate.

“Fraser was supposed to be looking after my friend,” Abou-Rass says. “That’s what he was getting paid for. But Tom was severely neglected, and Mr. Fraser was nowhere to be found.”

“I’m sure that the neglect and lack of supervision contributed to Tom’s death,” he adds. “But Fraser never checked on his well-being. Fraser’s only concern was to take his money. It never made sense. None of it did.”

This investigation reached out to Judges Hallmark, Callaghan, Ryan and O’Brien. No comment was received.

In a brief statement, Oakland County Court Administrator Edward Hutton said “I am unable to comment on matters pending before this court.”

Requests for comment to Carney, Fraser, Munger and Yun’s offices were not returned.

Calls to Hutt, Reynolds, Proctor and Fox were not returned.

*This investigation presented its findings to Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel’s staff on March 12, 2019. At that time, no comment was received.There have been no replies to further requests for comment.

There was no response to requests for comment made to Sunrise Senior Living and Notting Hill.

Gretchen Rachel Hammond is an award-winning freelance investigative journalist based out of Chicago. Her work has won or been nominated for four successive Chicago Press Club awards, been recognized by the National Association of Lesbian and Gay Journalists (NLGJA), and covered topics such as criminal justice, abuse at ICE detention facilities, and alleged discrimination on the part of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services leading to the unnecessary separation of children from their parents.

©gretchenrachelhammond2019

Click here for part four of five: The Consequences of Protecting Justice

Click here for part two

Click here for part one